The task ahead of the latest Housing Minister is immense. Since 1997, twenty of his predecessors from both parties have failed to get to grips with the inequality built in to our property market. Ownership levels are falling, rents and asking prices are soaring and for millions, home means living at the whim of a landlord or being hit by rocketing costs of ownership.

There’s no getting away from it.

The UK is experiencing a major housing crisis.

Whilst anyone who’s searched for somewhere to buy or rent recently will know this all too well, what’s less discussed is the broader impacts on society.

It’s an unprecedented shift creating massive changes to the way we live, work and think about the future. The UK’s housing crisis is one of the biggest challenges we face. Fewer and fewer people can afford high-quality accommodation that meets their needs.

So, what exactly is going on and what are the far-reaching consequences?

Is the UK really experiencing a housing crisis?

The UK is in the midst of unparalleled changes to its housing market, both in terms of home ownership and private rentals.

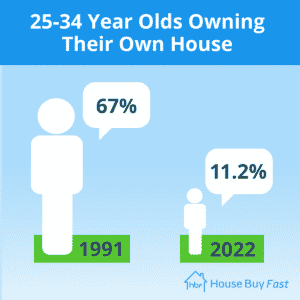

In 1991, 67% of 25-34 year olds owned their own home. Today, that’s just 11.2% (and 0.7% for anyone under 24). It’s not hard to see why either. According to Rightmove, asking prices increased by over £55,000 this year alone. How many people had a pay rise to match this?

Halifax reported average house prices were £289,099 in May 2022. That’s over ten times the median average UK salary of £25,971.

Over the past twenty years, the proportion of people living in rented accommodation doubled. According to the Homelet Rental Index, average UK monthly rents were £1,103 in May 2022 – up by over 10% on the same time last year. Prices are rising quicker in cities too, with more people returning to office-based work after the pandemic.

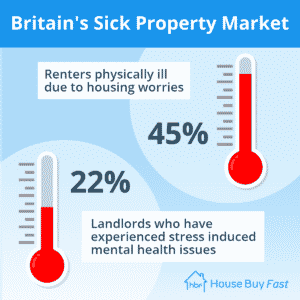

It’s not just the lack of home ownership at stake. The housing charity Shelter claims low quality housing impacts the health of over 20% of renters in England.

If you’re wondering what’s behind this, supply and demand play a big role. The lack of housing in the UK is pushing competition and prices ever higher, and wages aren’t keeping up.

Take land as another example. In the mid-1950s (expressed in recent prices), residential land cost around £150,000 per hectare. By the mid-1990s, this rose to 1.3 million, and by 2007 it was 5 million…

Shocking as they are, soaring rent, home buying and land prices don’t capture the scale of the problem. It’s not just a lack of supply, but also the types of homes on offer.

In a bid to capitalise on the buy-to-let housing boom, developers construct mostly two-bedroom homes. This is great if you’re after a two-person flat share (a lucrative option for landlords), but not so great for pretty much everyone else. It’s too large (and too expensive) for one person, and too small (often with a tiny garden, if at all) for a growing family.

What are the repercussions for society?

If you look, the effects of the UK’s housing crisis are everywhere.

With wages failing to keep pace with rents and house prices, vast chunks of the population spend a hefty portion of their income just to keep a roof over their heads.

Strain on families

Whilst this can bring generations closer together, it also puts strain on family groups. It creates a lack of bedrooms and living space, with many people delaying or deciding not to have children of their own as a result. Since the late 1980’s property boom birth rates have fallen from 13.7 per 1000 people to just 11.3. Housing issues are not the sole reason for this but have a significant part to play.

For younger children, growing up in cramped or poor-quality housing can be detrimental to their wellbeing, health and educational achievements. Indeed, children in poor-quality housing are twice as likely to fail core GCSE subjects.

Resentment of older generations capitalising on historically cheap housing has also bubbled up, with troubling implications for society as a whole.

Wealth inequality

A lack of space creates further wealth inequalities, making it difficult to work or study from home and limiting choice of location. Whether staying with parents or renting privately, exorbitant prices (especially in city centres) mean people often live far-away from family and work – resulting in fewer support networks and greater travel costs.

In turn, this can cause resentment of international immigration as well as shifts within the UK. In areas such as Cornwall or Devon locals have long struggled to compete with second-homers and anger is slowly growing.

What’s more, wealth becomes less dependent on work and endeavour. It’s instead based almost exclusively on where you’re born and whether you (or indeed a close relative) own property. For instance, inherit a three-bedroom house in central London, and you’ll make more money doing nothing than someone ever could working for the average UK income.

Risk aversion

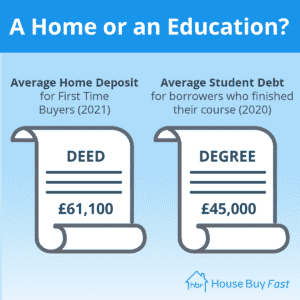

Spending so much money on rent and mortgages also means younger generations are less willing (or able) to take on student debt and entrepreneurial loans. Many prioritise saving a property deposit rather than university fees, funding a business idea or enriching their lives with travel.

With only a lucky few able to take on financial risks and investments, the downward spiral of stagnating wages, wealth inequalities and rising prices continue.

Could things be different?

Let’s imagine the alternatives.

If your rent or mortgage halved, what would you do differently?

Perhaps you’d work less, shift to a three-day week or a less well-paid, more rewarding profession? You might be able to invest in yourself more; eat better, exercise more, go on holidays with family or pay for that professional development course you’ve been thinking about for years.

If housing wasn’t such a pressing concern, we might see more creativity and risks in society. We could witness more involvement in peaceful protest and activism, with more time and energy spent on “big picture” issues such as environmentalism and social justice. With time currently spent discussing and experimenting with piece-meal ‘solutions’ to the crisis what more could be achieved by our governments and housing organisations?

At the moment, any increases in wealth or wages are immediately eaten up by price rises in the housing sector. It’s easy to see how this can impact the hopes and positivity of younger generations. If things were different, would we see more optimism and a generally more content society? Is at least part of the reason for our obsession with celebrity and social media an effort to distract ourselves from the lack of that most basic of human needs, a shelter, a home?

Whilst there are no easy solutions to the UK’s housing crisis, one thing’s certain, the current supply (both in terms of quantity and quality) isn’t meeting the needs of society. Whether buying or renting, surely people deserve better.

Given the implications for citizens all over the country, it’s time to start talking about what can be done to truly fix it – once and for all. The UK’s growing housing crisis needs to become more than just a dinner party discussion about house prices.

I hope that Marcus Jones, our new Housing Minister will see it for the outrage that it really is.